Making Bad Cows Good Down the Fence Part 1

Sometimes the feelings of being scared and excited can elicit the same physical response in our bodies.

When new challenges and opportunities show up in our riding lives, we may think we are feeling scared when what we really feel is excited. We might not have been taught how to welcome the thrill of a new opportunity, so we back off, feeling anxiety instead of awakening our courage to take on a new challenge.

The butterflies in our stomach or a rapidly beating heart are not necessarily a sign that we are afraid. Those very same feelings can be translated into excitement, curiosity, and passion.

There is nothing wrong with being afraid as long as we do not let it stop us from doing the things that excite us.

Most of us assume that brave people are fearless, but the truth is that they are simply more comfortable with fear because they face it on a regular basis. The more we do this, the more we feel excitement in the face of challenges rather than anxiety. The more we cultivate our ability to move forward instead of backing off, the more we trust ourselves to be able to handle the new opportunity, whether it’s going to a show, riding a colt for the first time or going down the fence.

When we feel our fear, we can remind ourselves that maybe we are actually excited. We can assure ourselves that this opportunity has come our way because we are meant to take it.

Framing things just a little differently can shift our mental state from one of resistance to one of openness. We can practice this new way of seeing things by saying aloud: I am really excited showing this horse for the first time! I am excited to go down the fence! Or, I am excited to have the opportunity to do something I have never done before.

As we do this, we will feel our energy shift from fear, which paralyzes, to excitement, which helps us direct that energy into growing and learning. Soon you’ll find yourself saying, “I can’t wait to go in the show pen and show my horse!”

Try it!

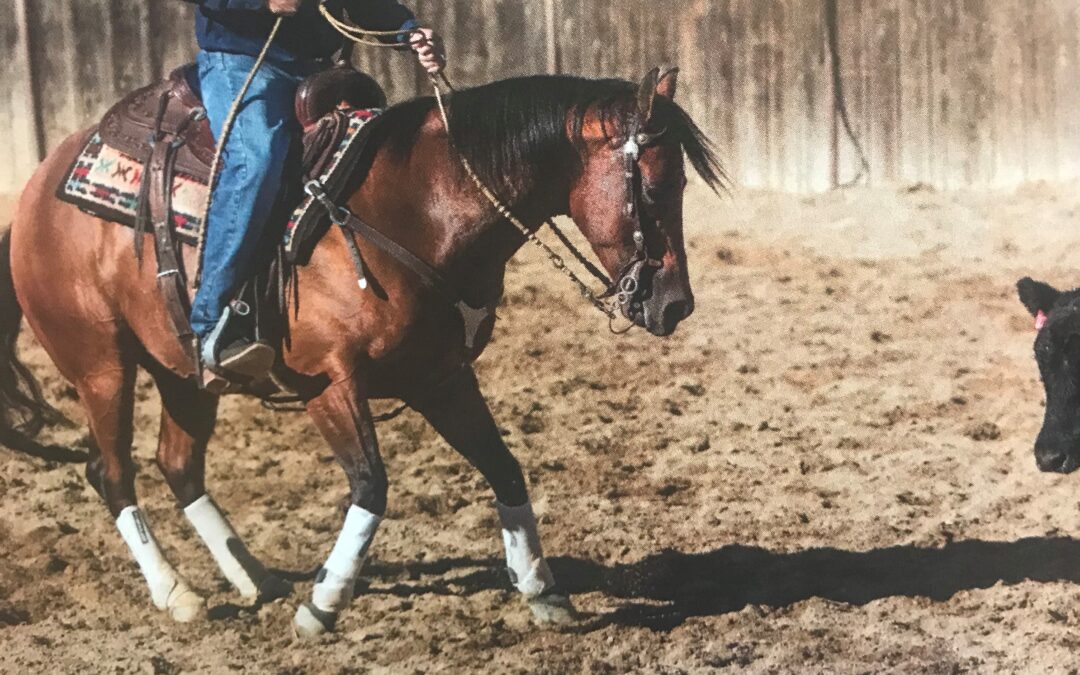

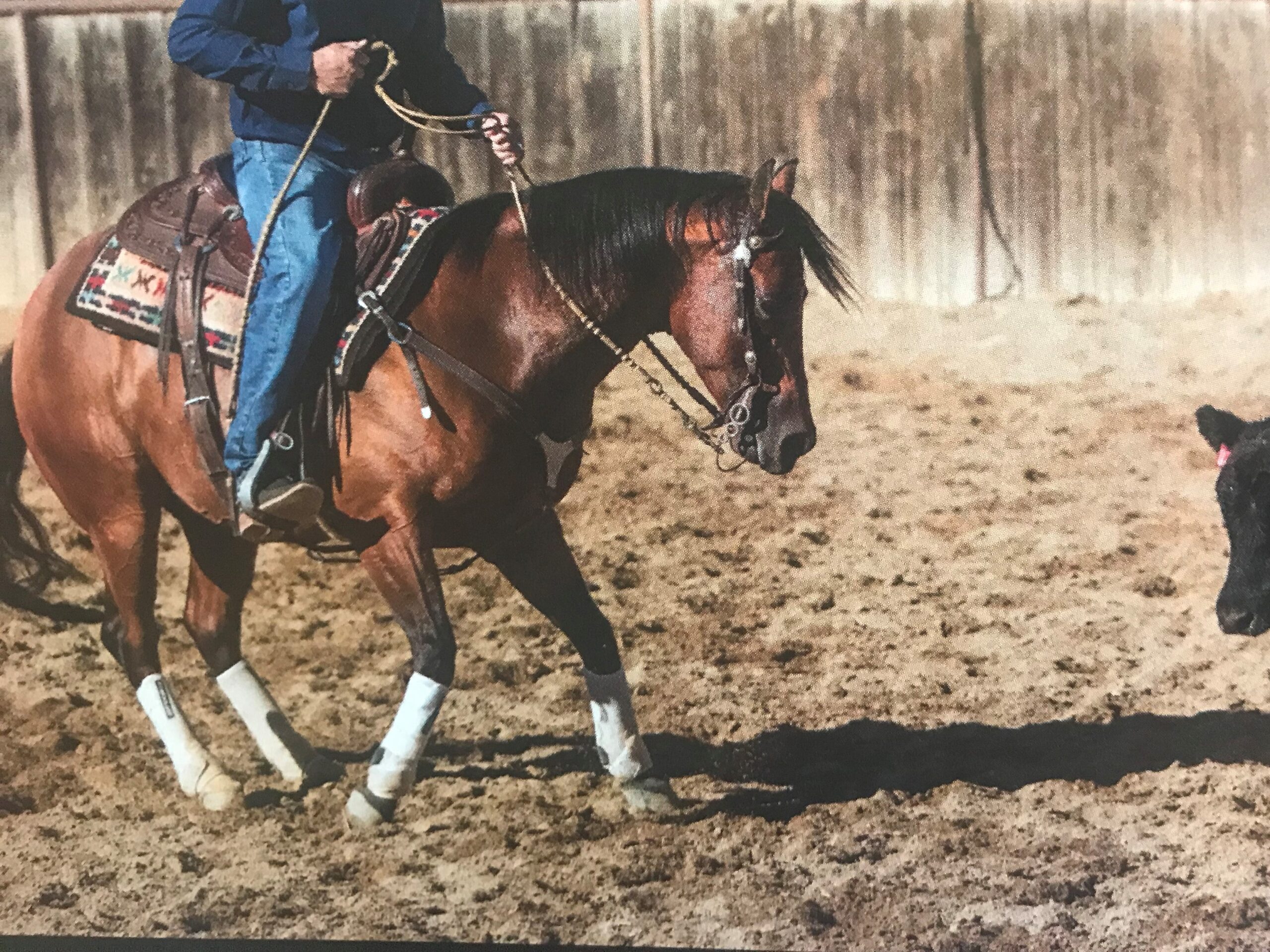

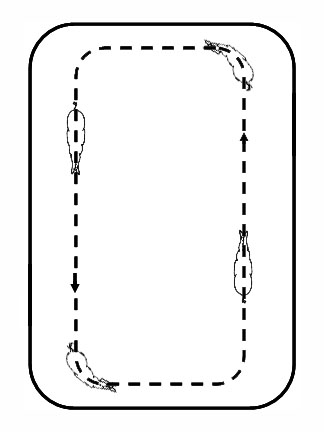

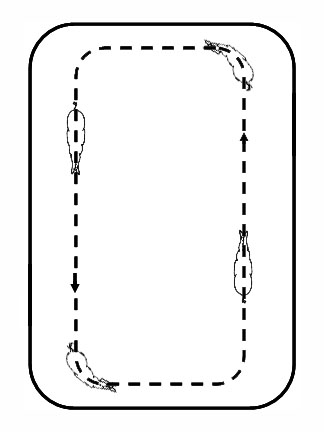

I’ll explain how to fence your horse at a lope; you can also perform it at a trot for the first few times.

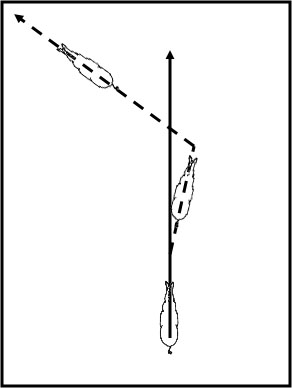

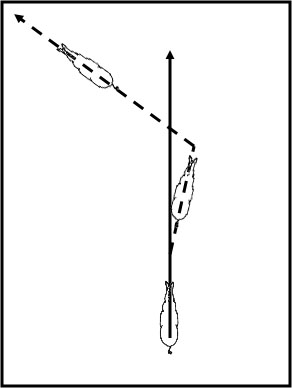

Begin by loping your horse around for a bit until he’s no longer fresh and is beginning to think about wanting to slow down and stop. Then lope a straight line slowly through the middle of the arena toward the end fence (be sure it’s a safe one). Use your legs and reins to keep him straight and perpendicular to the fence. Continue to drive with your legs right up to the fence. When you reach it, don’t pull on the reins; let the fence stop your horse. Then stand and rest for a moment, giving your horse a pat. You want the fence to become “a good place to be” in your horse’s mind. Then repeat the entire sequence.

As your horse becomes comfortable loping straight up to the fence and stopping, you can begin to say “Whoa” just before the stop.

Over time, as your horse’s confidence in this exercise grows, begin to build speed on the approach to the fence. If your horse starts to get nervous, go back to the last speed at which he was completely comfortable, then build even more slowly from there. And, whenever you’re stopped at the fence, spend as much time as needed until your horse is calm and relaxed.