You’re teaching all this through the repeated backing-up instead of repeated stopping. As a result, this is a terrific exercise for improving your horse’s stop without putting a lot of extra wear and tear on his hocks. It’s also something you can go back to when you begin to add speed if your horse starts to brace, as the Whoa-Back is a great way to soften him up.

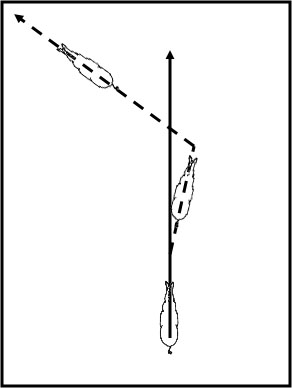

Here’s how: Start this exercise at an easy lope. Before you ask for the stop, make sure your horse isn’t just “motoring on”; in other words, he should have “at least one ear on you” (meaning he’s paying you some of his attention). Also, make sure he’s traveling straight and “in the box”—not leaning to one side or the other, or pushing on the reins.

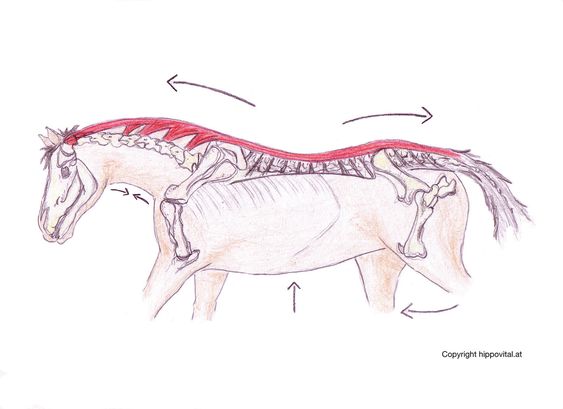

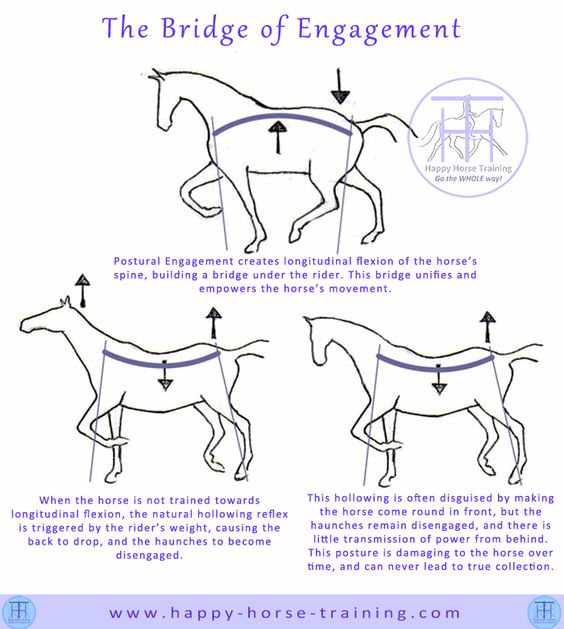

Then, sit down, and say “Whoa.” When your horse stops, back him off your hands a little more assertively than you have up to this point. To do this, hold your hands softly but firmly at belt level with enough pressure on them to keep him from going forward as you bump with both your legs to get him to come off the bit (i.e., you want him to rock back, pick his shoulders up, keep his head down, and stay soft in your hands). If he resists coming off the bit, up the ante by bumping more insistently with both legs in neutral position until he does, but not pulling harder.

Once he softens, back him up briskly and steadily until he feels as if he’s “getting back” (moving his feet more quickly) instead of just backing up. When he does, release all pressure and let him stand quietly for a moment. Then, without going forward, say “Whoa” again, take the slack out of the reins, and make him “get back” again. At this point, it’s important not to pull more or harder to get him to resume backing up; use your legs as necessary to drive him into the “wall” made by your hands, which then cause him to go back.

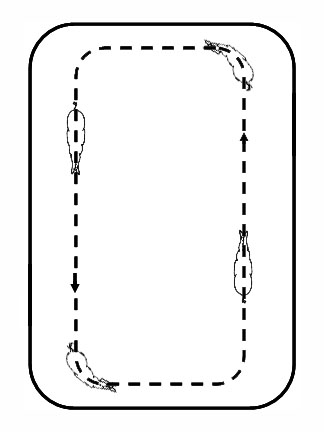

When he’s backing up as if he’s going somewhere (other than to a funeral, that is), let him stop and rest again. Keep going like this—backing, then resting—all the way across the arena if need be to get him responding willingly and lightly. Then pick up the lope and start again from the beginning.

Once he’s responding willingly at an easy lope, begin to speed him up. Be sure as you do, however, that you also increase his collection by using your legs in neutral position to push him into the bridle. He needs to drive from behind, rather than just “colt lope” on his front end. If he pulls the reins right out of your hands when you ask him to stop, he’s falling onto his front end—the result of not enough collection.

He’ll start to read your body better and softly be backing before all the slack comes out of your reins. It will feel effortless and resistant free. That’s a good time to go take a trail ride and try it out under different circumstances.

Let me know how it works for you!